“The language people speak in the corridors of power,” former Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter once observed, “is not economics or politics. It is history.”

In a recent academic article, I showed how true this was after both the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001 and the “9/15” bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in 2008. Policy makers used all kinds of historical analogies as they reacted. “The Pearl Harbor of the 21st century took place today,” President George W. Bush noted in his diary, late on the night of the attacks, to give just one example, though many other parallels were drawn in the succeeding days, from the Civil War to the Cold War.

Seven years later, Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke and New York Fed President Tim Geithner were the first members of the Federal Open Market Committee to appreciate that, without drastic measures, they risked re-running the Great Depression.

What kind of history is informing today’s decisions in Washington as the war in Ukraine nears the conclusion of its first month? A few clues have emerged.

“American officials are divided on how much the lessons from Cold War proxy wars, like the Soviet Union’s war in Afghanistan, can be applied to the ongoing war in Ukraine,” David Sanger reported for the New York Times on Saturday.

According to Sanger, who cannot have written his piece without high-level sources, the Biden administration “seeks to help Ukraine lock Russia in a quagmire without inciting a broader conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary or cutting off potential paths to de-escalation … CIA officers are helping to ensure that crates of weapons are delivered into the hands of vetted Ukrainian military units, according to American officials. But as of now, Mr. Biden and his staff do not see the utility of an expansive covert effort to use the spy agency to ferry in arms as the United States did in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union during the 1980s.”

I have evidence from other sources to corroborate this. “The only end game now,” a senior administration official was heard to say at a private event earlier this month, “is the end of Putin regime. Until then, all the time Putin stays, [Russia] will be a pariah state that will never be welcomed back into the community of nations. China has made a huge error in thinking Putin will get away with it. Seeing Russia get cut off will not look like a good vector and they’ll have to re-evaluate the Sino-Russia axis. All this is to say that democracy and the West may well look back on this as a pivotal strengthening moment.”

I gather that senior British figures are talking in similar terms. There is a belief that “the U.K.’s No. 1 option is for the conflict to be extended and thereby bleed Putin.” Again and again, I hear such language. It helps explain, among other things, the lack of any diplomatic effort by the U.S. to secure a cease-fire. It also explains the readiness of President Joe Biden to call Putin a war criminal.

Now, I may be too pessimistic. I would very much like to share Francis Fukuyama’s optimism that “Russia is heading for an outright defeat in Ukraine.” Here is his bold prediction from March 10 (also here):

The collapse of their position could be sudden and catastrophic, rather than happening slowly through a war of attrition. The army in the field will reach a point where it can neither be supplied nor withdrawn, and morale will vaporize. … Putin will not survive the defeat of his army … A Russian defeat will make possible a “new birth of freedom,” and get us out of our funk about the declining state of global democracy. The spirit of 1989 will live on, thanks to a bunch of brave Ukrainians.

From his laptop to God’s ears.

I can see why so many Western observers attach a high probability to this scenario. There is no question that the Russian invasion force has sustained very high casualties and losses of equipment. Incredibly, Komsomolskaya Pravda, a pro-Kremlin Russian newspaper, just published Russian Ministry of Defense numbers indicating 9,861 Russian soldiers killed in Ukraine and 16,153 wounded. (The story was quickly removed.) By comparison, 15,000 Soviet troops died and 35,000 were wounded in 10 years in Afghanistan.

Moreover, there is ample evidence that their logistics is a mess, exemplified by the many supply trucks that have simply been abandoned because their tires or engines gave out. By these measures, Ukraine does seem to be winning the war, as Phillips O’Brien and Eliot A. Cohen have argued. History also provides numerous cases of authoritarian regimes that fell apart quite rapidly in the face of military reverses — think of the fates of Saddam Hussein and Moammar Al Qaddafi, or the Argentine junta that invaded the Falklands almost exactly 40 years ago.

It would indeed be wonderful if the combination of attrition in Ukraine and a sanctions-induced financial crisis at home led to Putin’s downfall. Take that, China! Just you try the same trick with Taiwan — which, by the way, we care about a lot more than Ukraine because of all those amazing semiconductors they make at Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.

The fascinating thing about this strategy is the way it combines cynicism and optimism. It is, when you come to think of it, archetypal Realpolitik to allow the carnage in Ukraine to continue; to sit back and watch the heroic Ukrainians “bleed Russia dry”; to think of the conflict as a mere sub-plot in Cold War II, a struggle in which China is our real opponent.

The Biden administration not only thinks it’s doing enough to sustain the Ukrainian war effort, but not so much as to provoke Putin to escalation. It also thinks it’s doing enough to satisfy public opinion, which has rallied strongly behind Ukraine, but not so much as to cost American lives, aside from a few unlucky volunteers and journalists.

The optimism, however, is the assumption that allowing the war to keep going will necessarily undermine Putin’s position; and that his humiliation in turn will serve as a deterrent to China. I fear these assumptions may be badly wrong and reflect a misunderstanding of the relevant history.

Prolonging the war runs the risk not just of leaving tens of thousands of Ukrainians dead and millions homeless, but also of handing Putin something that he can plausibly present at home as victory. Betting on a Russian revolution is betting on an exceedingly rare event, even if the war continues to go badly for Putin; if the war turns in his favor, there will be no palace coup.

As for China, I believe the Biden administration is deeply misguided in thinking that its threats of secondary sanctions against Chinese companies will deter President Xi Jinping from providing economic assistance to Russia.

Begin with the military situation, which Western analysts consistently present in too favorable a light for the Ukrainians. As I write, it is true that the Russians seem to have put on hold their planned encirclement of Kyiv, though fighting continues on the outskirts of the city. But the theaters of war to watch are in the east and the south.

In the east, according to military experts whom I trust, there is a significant risk that the Ukrainian positions near the Donbas will come under serious threat in the coming weeks. In the south, a battalion-sized Chechen force is closing in on the besieged and 80%-destroyed city of Mariupol. The Ukrainian defenders lack resupply outlets and room for tactical breakout. In short, the fall of Mariupol may be just days away. That in turn will free up Russian forces to complete the envelopment of the Donbas front.

The next major targets in the south lie further west: Mykolayiv, which is inland, northwest of Kherson, and then the real prize, the historic port city of Odesa. It doesn’t help the defenders that a large storm in the northern Black Sea on Friday did considerable damage to Ukrainian sea defenses by dislodging mines.

Also on Friday, the Russians claim, they used a hypersonic weapon in combat for the first time: a Kinzhal air-launched missile which was used to take out an underground munitions depot at Deliatyn in western Ukraine. They could have achieved the same result with a conventional cruise missile. The point was presumably to remind Ukraine’s backers of the vastly superior firepower Russia has at its disposal. Thus far, around 1,100 missiles have struck Ukraine. There are plenty more where they came from.

And, of course, Putin has the power — unlike Saddam or Qaddafi — to threaten to use nuclear weapons, though I don’t believe he needs to do more than make threats, given that the conventional war is likely to turn in his favor. The next blow will be when Belarusian forces invade western Ukraine from the north, which the Ukrainian general staff expects to happen in the coming days, and which could pose a threat to the supply of arms from Poland.

In any case, Putin has other less inflammatory options if he chooses to escalate. Cyberwarfare thus far has been Sherlock Holmes’s dog that didn’t bark. On Monday the Biden administration officially warned the private sector: “Beware of the dog.” Direct physical attacks on infrastructure (e.g., the undersea cables that carry the bulk of global digital traffic) are also conceivable.

I fail to see in current Western strategizing any real recognition of how badly this war could go for Ukraine in the coming weeks. The incentive for Putin is obviously to create for himself a stronger bargaining position than he currently has before entering into serious negotiations. The Ukrainians have shown their cards. They are ready to drop the idea of NATO membership; to accept neutrality; to seek security guarantees from third parties; to accept limits on their own military capability.

What is less clear is where they stand on the future status of Crimea and the supposedly independent republics of Donetsk and Luhansk. It seems obvious that Putin needs more than just these to be able to claim credibly to have won his war. It seems equally obvious that, if they believe they are winning, the Ukrainians will not yield a square mile of territory. Control of the Black Sea coast would give Putin the basis from which to demand further concessions, notably a “land bridge” from Crimea to Russia.

Meanwhile, the mainly financial sanctions imposed on Russia are doing their intended work, in causing something like a nationwide bank run and consumer goods shortages. Estimates vary as to the scale of the economic contraction — perhaps as much as a third, recalling the depression conditions that followed the Soviet collapse in 1991.

Yet, so long as European Union countries refuse to impose an energy embargo on Russia, Putin’s regime continues to receive around $1.1 billion a day from the EU in oil and gas receipts. I remain skeptical that the sanctions as presently constituted can either halt the Russian war machine or topple Putin. Why has the ruble not fallen further and even rallied against the euro last week?

Remember, both sides get to apply history. The Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy is a master of the art, carefully tailoring his speeches to each national parliament he addresses, effectively telling one country after another: “Our history is your history. We are you.” He gave the Brits Churchill, the Germans the Berlin Wall, the Yanks Martin Luther King Jr., and the Israelis the Holocaust.

Putin applies history in a diametrically opposite way. “The president has completely lost interest in the present,” the Russian journalist Mikhail Zygar argued in a recent New York Times piece. “The economy, social issues, the coronavirus pandemic, these all annoy him. Instead, he and [his adviser Yuri] Kovalchuk obsess over the past.”

I can see that. Putin’s recent pseudo-scholarly writing — on the origins of World War II and “On the Historical Unity of the Russians and Ukrainians” — confirm the historical turn in his thought.

I disagree with the former Russian foreign minister, Andrey Kozyrev, who told the Financial Times that, for Putin and his cronies, “the cold war never stopped.” That is not the history that interests Putin. As the Bulgarian political scientist Ivan Krastev told Der Spiegel, Putin “expressed outrage that the annexation of the Crimea had been compared with Hitler’s annexation of the Sudetenland in 1938. Putin lives in historic analogies and metaphors. Those who are enemies of eternal Russia must be Nazis.” Moreover:

The hypocrisy of the West has become an obsession of his, and it is reflected in everything the Russian government does. Did you know that in parts of his declaration on the annexation of Crimea, he took passages almost verbatim from the Kosovo declaration of independence, which was supported by the West? Or that the attack on Kyiv began with the destruction of the television tower just as NATO attacked the television tower in Belgrade in 1999?

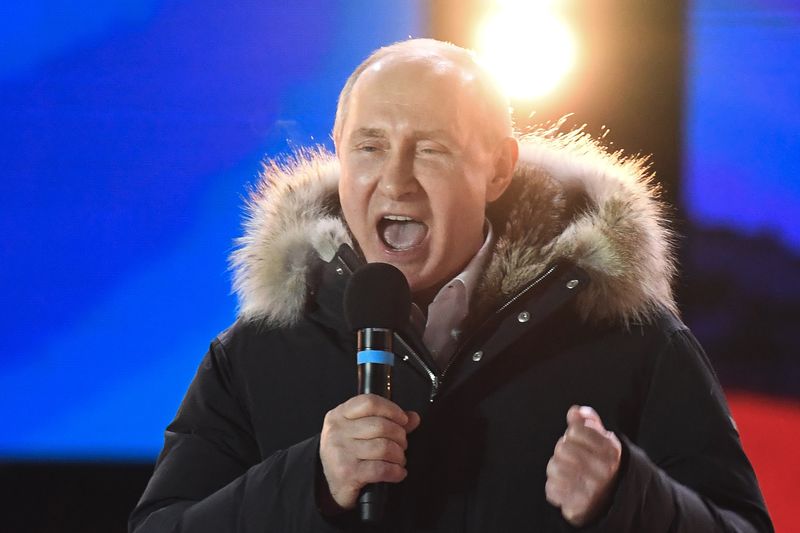

Yet such recent history is less significant to Putin than the much older history of Russia’s imperial past. I have made this argument here before. Fresh evidence that Putin’s project is not the resurrection of the Soviet Union, but looks back to tsarist imperialism and Orthodoxy, was provided by his speech at the fascistic rally held on Friday at Moscow’s main football stadium. Its concluding allusion to the tsarist admiral Fyodor Ushakov, who made his reputation by winning victories in the Black Sea, struck me as ominous for Odesa.

The Chinese also know how to apply history to contemporary problems, but they do it in a different way again. While Putin wants to transport post-Soviet Russia back into a mythologized tsarist past, Xi remains the heir to Mao Zedong, and one who aspires to a place alongside him in the Chinese Communist Party’s pantheon. In their two-hour call on Friday, according to the Chinese Foreign Ministry read-out, Biden told Xi:

50 years ago, the US and China made the important choice of issuing the Shanghai Communique. Fifty years on, the US-China relationship has once again come to a critical time. How this relationship develops will shape the world in the 21st century. Biden reiterated that the US does not seek a new Cold War with China; it does not aim to change China’s system; the revitalization of its alliances is not targeted at China; the US does not support “Taiwan independence”; and it has no intention to seek a conflict with China.

To judge by Xi’s response, he believes not one word of Biden’s assurances. As he replied:

The China-US relationship, instead of getting out of the predicament created by the previous US administration, has encountered a growing number of challenges. …

In particular … some people in the US have sent a wrong signal to “Taiwan independence” forces. This is very dangerous. Mishandling of the Taiwan question will have a disruptive impact on the bilateral ties … The direct cause for the current situation in the China-US relationship is that some people on the US side have not followed through on the important common understanding reached by the two Presidents …

Xi concluded with a Chinese saying: “He who tied the bell to the tiger must take it off.” Make of that what you will, but it didn’t strike me as very encouraging to those in Team Biden who have been pushing a hawkish line toward China.

The China hawks in the administration — notably Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi at the National Security Council — do not like the term “Cold War II.” But Doshi’s recent book “The Long Game” (which I reviewed here) is essentially a manual for the containment of China — the nearest thing we are likely to get to George Kennan’s foundational Long Telegram and “X” article in Foreign Affairs.

And National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan did not make himself popular at last Monday’s marathon meeting with his Chinese counterpart, Yang Jiechi, by threatening secondary sanctions against a list of Chinese companies the U.S. will be watching for signs that they are trading with Russia. If Benn Steill and Benjamin Della Rocca of the Council on Foreign Relations are right, the Chinese have already helped Russia hide some of its foreign exchange reserves from financial sanctions.

Judging by his weekend interview in the Wall Street Journal, a member of President Donald Trump’s NSC, Matthew Pottinger, is now more than content to call a cold war by its real name. I agree: The invasion of Ukraine in many ways resembles the invasion of South Korea by North Korea in 1950.

I would put it like this: Cold War II is like a strange mirror-image of Cold War I. In the First Cold War, the senior partner was Russia, the junior partner was China — now the roles are reversed. In Cold War I, the first hot war was in Asia (Korea) — now it’s in Europe (Ukraine). In Cold War I, Korea was just the first of many confrontations with aggressive Soviet-backed proxies — today the crisis in Ukraine will likely be followed by crises in the Middle East (Iran) and Far East (Taiwan).

But there’s one very striking contrast. In Cold War I, President Harry Truman’s administration was able to lead an international coalition with a United Nations mandate to defend South Korea; now Ukraine has to make do with just arms supplies. And the reason for that, as we have seen, is the Biden administration’s intense fear that Putin may escalate to nuclear war if U.S. support for Ukraine goes too far.

That wasn’t a concern in 1950. Although the Soviets conducted their first atomic test on August 29, 1949, less than a year before the outbreak of the Korean War, they were in no way ready to retaliate if (as General Douglas MacArthur recommended) the U.S. had used atomic bombs to win the Korean War.

History talks in the corridors of power. But it speaks in different voices, according to where the corridors are located. In my view — and I really would love to be wrong about this — the Biden administration is making a colossal mistake in thinking that it can protract the war in Ukraine, bleed Russia dry, topple Putin and signal to China to keep its hands off Taiwan.

Every step of this strategy is based on dubious history. Ukraine is not Afghanistan in the 1980s, and even if it were, this war isn’t going to last 10 years — more like 10 weeks. Allowing Ukraine to be bombed to rubble by Putin is not smart; it creates the chance for him to achieve his goal of rendering Ukrainian independence unviable. Putin, like most Russian leaders in history, will most likely die of natural causes.

And China watches all this with a growing sense of certainty that it is not up against the U.S. of Truman and Kennan. For that America — the one that so confidently waged the opening phase of Cold War I — is itself now history.